Sarasota Journal – 27 Ene 1971

Here’s another deal from Freddie Sheinwold’s Pocket Book of Bridge Puzzles Number 6, which after we are through perusing it, we shall pass on to some of you aficionados. The moral of this story concerns the difference between one intermediate card and another, and yet one never counts such cards in even the most sophisticated point-counting methods.

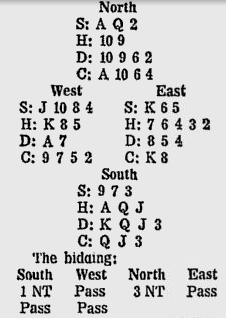

South dealer Both sides vulnerable

The bidding was standard as was the opening lead from West — the jack of spades.

The crucial decision for Declarer was on this first trick. If Declarer played the queen, as some people would do automatically, down goes McGinty. East would take the king and continue the suit to force out dummy’s ace.

Then West would be sure to gain the lead with the ace of diamonds to cash the thirteenth spade, and in addition the defense would he bound to take either the king of hearts or the king of clubs to beat the contract.

Declarer correctly went up with dummy’s ace of spades on the first trick. That nine of spades he held in his own hand was a crucial card. The eight would have been too small, as Baby Bear’s bowl of porridge was for Goldilocks. (Wasn’t it?)

Now when Declarer played a diamond to knock out the ace, West was hound to give Declarer two spade tricks if he continued spades. If West came on with a low spade, Declarer would duck in dummy and East would have to play the king to beat the nine in the closed hand. If West led the ten of spades, the queen would go on from dummy and if East covered, Declarer’s nine would be set up for a stopper.

With two spade tricks assured, Declarer could go after the clubs and make sure of nine tricks with three clubs, three diamonds, two spades, and one heart. If West had abandoned spades, Declarer would have time to try the heart finesse as well. So you see, in bridge, it is better to be behind the nine-spot than behind the eight-spot, points or no points.