Source: Around the World in 80 Hands By Zia Mahmood, David Burn

Matthew Granovetter, editor of one of the best magazines around, Bridge Today, once wrote a wonderful piece describing the agony of losing a bridge tournament. In it, he described the terrible pain resulting from hearing the Shriek that erupts, animal-like, from a team that discovers on comparing scores that it has won the tournament. When you hear that Shriek, you don’t bother to finish your own scoring, because whatever you have is not enough. If you had scored up first, and discovered that you’d lost before you heard the Shriek, it wouldn’t have hurt nearly as badly. Being extremely sensitive in that department — losing, I mean — I’ve tried fastidiously to avoid hearing it. I nearly always run out of the room after a session faster than the opponents, and have even learned to score while keeping a running total in order to beat them to it. Sometimes, discovering that I have lost before the opponents know that they have won, I have let out a psychic Shriek — to vent my frustration and strike terror into their hearts.

I’m happy to say that I was doing pretty well with this policy, until the Reisinger Team event in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. First, let me tell you about our team for this tournament. The dramatis per-sonae were: Michael Rosenberg — a Scottish emigre whose years in New York have done nothing to change his wholly unintelligible accent. Sam Lev — a wild Israeli terrorist, with a beard. Chris Compton — a tamer version of Lev with a thinner beard. Mark Molson — a last-minute addition whom we all thought was a palooka until he won the Blue Ribbon pairs the day before, so we immediately revised our opinion. We also owed him a lot of money from the morning’s golf game. We were a bunch of misfits, brought together by fate with no partnership understandings. How could we lose? I, as team captain, was responsible for ensuring that everybody followed my example. No going to sleep before 3:00 a.m., get up early to play golf, drink wine with dinner between sessions and, above all, keep conventions to the minimum. Unfamiliar partner-ships can often reap big rewards — no understandings, no misun-derstandings. This proved itself early on when Lev, holding: ![]()

responded 5NT to Mark Molson’s opening 4![]() . Molson, who did not know what 5NT meant because he and Lev had not discussed it, jumped professionally to 7

. Molson, who did not know what 5NT meant because he and Lev had not discussed it, jumped professionally to 7![]() with:

with: ![]()

Mark intended his bid to show two top hearts — he jumped to 7![]() in case his partner had some grand slam other than hearts in mind. Lev fenced delicately with 7

in case his partner had some grand slam other than hearts in mind. Lev fenced delicately with 7![]() and Molson, having no idea what was happening, returned to 7

and Molson, having no idea what was happening, returned to 7![]() . He made this easily, dropping Alan Sontag’s doubleton

. He made this easily, dropping Alan Sontag’s doubleton ![]() Q and his jaw at the same time. You’d never see Stansby and Martel getting to 7

Q and his jaw at the same time. You’d never see Stansby and Martel getting to 7![]() on these cards, now would you? Later, someone dared to suggest that Lev’s 5NT was not a thing of beauty. «I am not,» said Sam, «here to bid beautiful contracts. I am here to win the board.» Paired at times with both Molson and Compton, Lev played what I call ‘Israeli Savage, an aggressive ver-sion of `Paki Savage. Basically, the system has two rules:

on these cards, now would you? Later, someone dared to suggest that Lev’s 5NT was not a thing of beauty. «I am not,» said Sam, «here to bid beautiful contracts. I am here to win the board.» Paired at times with both Molson and Compton, Lev played what I call ‘Israeli Savage, an aggressive ver-sion of `Paki Savage. Basically, the system has two rules:

1) Bid notrump, and 2) Punish your partner and your opponents alike without mercy. For those of you who don’t know how the Reisinger works, let me explain. The form of scoring is ‘board-a-match’ — that is, each deal is compared against your opponents only, counting one point for a win, a half point for a draw and none for a loss. To win a board, it does not matter how high or low your score is, as long as it beats the opponents at the other table. If you make 7![]() for 2210 while your opponents go one down for 100, you win the board. If on the next deal they make 2

for 2210 while your opponents go one down for 100, you win the board. If on the next deal they make 2![]() with an overtrick for 140 while your team-mates beat 1NT a trick for 100 only, you lose the board right back again. It’s like playing matchpointed pairs in a field of two tables —no matter what the aggregate swing, you score one or a half or zero. Our team did not score many halves. We were rarely in the same contract as the players at the other table. Card play is of paramount importance at this form of scoring. Here are some examples:

with an overtrick for 140 while your team-mates beat 1NT a trick for 100 only, you lose the board right back again. It’s like playing matchpointed pairs in a field of two tables —no matter what the aggregate swing, you score one or a half or zero. Our team did not score many halves. We were rarely in the same contract as the players at the other table. Card play is of paramount importance at this form of scoring. Here are some examples:

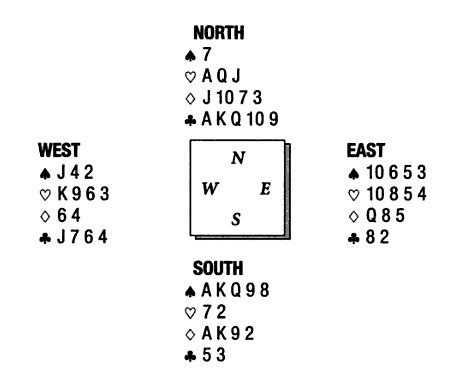

After a long sequence in which every suit was bid at least once, some of them twice, and North made a cuebid in hearts, South arrived in 6![]() . I led the

. I led the ![]() 9 from the West hand — slightly primitive, but the spectators were getting restless and I had to lead something. Declarer put up the

9 from the West hand — slightly primitive, but the spectators were getting restless and I had to lead something. Declarer put up the ![]() A from dummy and cashed three rounds of spades to discard the queen and jack of hearts from the North hand. On the first round of spades, I dropped the jack. Why? Why not? It could not hurt. However, I could not see that it would help either — but wait. Declarer discarded dummy’s hearts as planned, ruffed a heart, and ran the

A from dummy and cashed three rounds of spades to discard the queen and jack of hearts from the North hand. On the first round of spades, I dropped the jack. Why? Why not? It could not hurt. However, I could not see that it would help either — but wait. Declarer discarded dummy’s hearts as planned, ruffed a heart, and ran the ![]() J. When this held, he led another diamond to his nine. This was the position:

J. When this held, he led another diamond to his nine. This was the position:

The 6![]() contract was cold, but because of the board-a-match scoring, the overtrick was crucial if our teammates were (for once) in the same contract. You can see that declarer could ruff a spade in dummy to ensure thirteen tricks. However, because I had dropped the

contract was cold, but because of the board-a-match scoring, the overtrick was crucial if our teammates were (for once) in the same contract. You can see that declarer could ruff a spade in dummy to ensure thirteen tricks. However, because I had dropped the ![]() J on the first round, South was convinced that my spades had been

J on the first round, South was convinced that my spades had been ![]() J10xx, and that a spade would be overruffed by East who was marked with the

J10xx, and that a spade would be overruffed by East who was marked with the ![]() Q. That seemingly silly play of the

Q. That seemingly silly play of the ![]() J at trick two had become important after all. Reasonably enough, declarer drew the last trump and played for the

J at trick two had become important after all. Reasonably enough, declarer drew the last trump and played for the ![]() J to fall. It did not, and he made twelve tricks only, so that we won the board. Sometimes, there are opportunities to play a falsecard without cost. Here, once declarer had refused the heart finesse at Trick 1 and started to cash spades before drawing trumps, it was obvious that he held

J to fall. It did not, and he made twelve tricks only, so that we won the board. Sometimes, there are opportunities to play a falsecard without cost. Here, once declarer had refused the heart finesse at Trick 1 and started to cash spades before drawing trumps, it was obvious that he held ![]() AKQ and intended to throw dummy’s hearts on his winners. That being so, my

AKQ and intended to throw dummy’s hearts on his winners. That being so, my ![]() J was due to fall uselessly on the third round —so why not drop it on the first, and see if I could cause some confusion? The most subtly effective type of falsecard occurs when an honor that is due to fall anyway is dropped earlier than it has to be. You’d be amazed at the unexpected gains this can produce. Between sessions on Saturday my teammate Lev gave me some coaching. He advised me that if, as declarer, I always took the simple line rather than the esoteric, we would win the tournament. That night I had to play 6

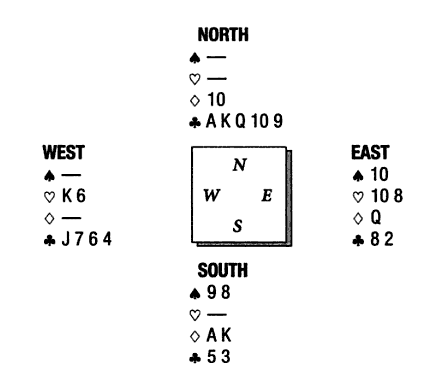

J was due to fall uselessly on the third round —so why not drop it on the first, and see if I could cause some confusion? The most subtly effective type of falsecard occurs when an honor that is due to fall anyway is dropped earlier than it has to be. You’d be amazed at the unexpected gains this can produce. Between sessions on Saturday my teammate Lev gave me some coaching. He advised me that if, as declarer, I always took the simple line rather than the esoteric, we would win the tournament. That night I had to play 6![]() on these cards:

on these cards:

After a heart lead, I ducked, and won the heart continuation with the ![]() A. A trump to the

A. A trump to the ![]() Q and a heart ruff back to my hand allowed me to draw the remaining trumps with the ace and king. Then I played on diamonds, to ruff out the suit — but East had four diamonds and West none, so I had annoyingly to lose a trick to East’s

Q and a heart ruff back to my hand allowed me to draw the remaining trumps with the ace and king. Then I played on diamonds, to ruff out the suit — but East had four diamonds and West none, so I had annoyingly to lose a trick to East’s ![]() K in the end. After the session, my Israeli friend chastised me for not first cashing the

K in the end. After the session, my Israeli friend chastised me for not first cashing the ![]() A when I was in dummy with the

A when I was in dummy with the ![]() Q. Then, I could ruff a heart and play all the trumps. East, who held four diamonds and the

Q. Then, I could ruff a heart and play all the trumps. East, who held four diamonds and the ![]() K, would be squeezed on the last spade. «What’s the matter with you?» grumbled Lev. «You never heard of the Vienna Coup?» Is that what he meant by following the simple line? In fact, it was not until after the session that we realized the correct play. Leave the

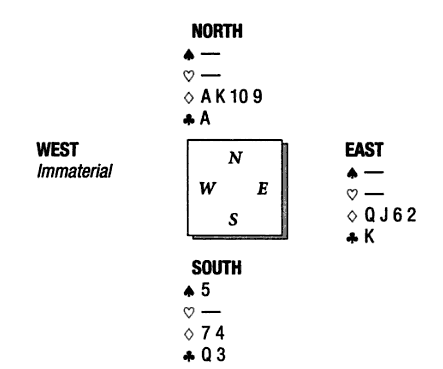

K, would be squeezed on the last spade. «What’s the matter with you?» grumbled Lev. «You never heard of the Vienna Coup?» Is that what he meant by following the simple line? In fact, it was not until after the session that we realized the correct play. Leave the ![]() A in dummy, do not touch diamonds, but play out all the spades except the last, coming down to this position:

A in dummy, do not touch diamonds, but play out all the spades except the last, coming down to this position:

Since declarer’s intention is to ruff out the diamond suit, and he cannot cope with a 4-0 break, it costs nothing to play all but one spade before attacking diamonds. When he eventually leads a diamond to dummy, the bad break is revealed, and South has no option but to cash the ![]() A and pray that East has been forced to bare the

A and pray that East has been forced to bare the ![]() K on the penultimate trump in order to keep four diamonds. Somehow, we were leading the field going into the final session. Luckily, bad weather had forced Benito Garozzo and I to abandon our golf challenge (luckily for me, at any rate, for when it was resumed a few months later, he beat me by five holes), so I was able to concentrate fully at the table — in theory, at any rate. For the last few rounds, Michael Rosenberg and I played on Vugraph — we were at a table surrounded by television cameras, relaying our bids and plays to an audience with our every move followed by expert commentators. I think that people underestimate the effect that Vugraph has on major events. I am sure that some players become nervous in the spotlight, and you can’t help but under perform at bridge if you’re nervous. Others feel more comfortable, more confident, and I thought that playing on Vugraph was to our benefit, as we were perhaps more used to the lights than some. We had an average final session, and thought that it would be touch and go whether we won or not. When we came to the last deal of the night, we were both subject to the ‘let’s hurry up and compare scores feeling. This, though understandable after three days of the fiercest bridge you can imagine, was not a very professional outlook. Here is my confession:

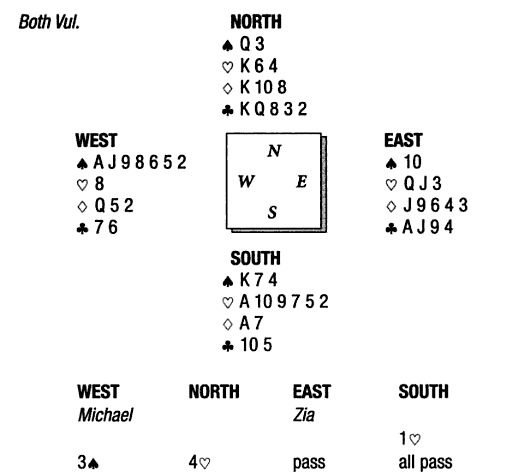

K on the penultimate trump in order to keep four diamonds. Somehow, we were leading the field going into the final session. Luckily, bad weather had forced Benito Garozzo and I to abandon our golf challenge (luckily for me, at any rate, for when it was resumed a few months later, he beat me by five holes), so I was able to concentrate fully at the table — in theory, at any rate. For the last few rounds, Michael Rosenberg and I played on Vugraph — we were at a table surrounded by television cameras, relaying our bids and plays to an audience with our every move followed by expert commentators. I think that people underestimate the effect that Vugraph has on major events. I am sure that some players become nervous in the spotlight, and you can’t help but under perform at bridge if you’re nervous. Others feel more comfortable, more confident, and I thought that playing on Vugraph was to our benefit, as we were perhaps more used to the lights than some. We had an average final session, and thought that it would be touch and go whether we won or not. When we came to the last deal of the night, we were both subject to the ‘let’s hurry up and compare scores feeling. This, though understandable after three days of the fiercest bridge you can imagine, was not a very professional outlook. Here is my confession:

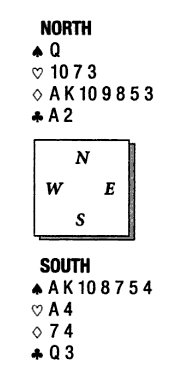

Michael led the ![]() 2. From my point of view, this could have been a singleton — but to tell you the truth, my point of view at that time consisted only oh ‘Let’s play fast, so we can go and compare scores — and let’s avoid the deathly Shriek of the winning team if we lose: Declarer won the diamond lead in his hand with the

2. From my point of view, this could have been a singleton — but to tell you the truth, my point of view at that time consisted only oh ‘Let’s play fast, so we can go and compare scores — and let’s avoid the deathly Shriek of the winning team if we lose: Declarer won the diamond lead in his hand with the ![]() A (two, eight, nine, ace). He drew two rounds of trumps — he should probably have played on spades or clubs first. On the second round of hearts, Michael discarded the

A (two, eight, nine, ace). He drew two rounds of trumps — he should probably have played on spades or clubs first. On the second round of hearts, Michael discarded the ![]() 8. Now, declarer led a club from his hand, Michael played the

8. Now, declarer led a club from his hand, Michael played the ![]() 7, and dummy played the

7, and dummy played the ![]() Q. In this sort of position, it’s nearly always right for me to hold up the

Q. In this sort of position, it’s nearly always right for me to hold up the ![]() A. That gives the defense control of activities, and provides time for both defenders to understand what’s happening around the table. This was, in short, an obvious hold-up situation. However, ducking was the ‘slow’ defense, and I was very anxious to find out if we’d won the event or blown it. So I made the feeble play of winning the

A. That gives the defense control of activities, and provides time for both defenders to understand what’s happening around the table. This was, in short, an obvious hold-up situation. However, ducking was the ‘slow’ defense, and I was very anxious to find out if we’d won the event or blown it. So I made the feeble play of winning the ![]() A to cash the

A to cash the ![]() Q. This was not in itself fatal, but look what happened. Michael threw the

Q. This was not in itself fatal, but look what happened. Michael threw the ![]() 9 — perhaps that cancelled the earlier encouraging meaning of the

9 — perhaps that cancelled the earlier encouraging meaning of the ![]() 8, but who knew? A good defender should always try to make things easy for partner. In my heart, I knew I ought to play a diamond, making everything clear. But declarer had only shown up with two aces so far —surely, I thought, he had the

8, but who knew? A good defender should always try to make things easy for partner. In my heart, I knew I ought to play a diamond, making everything clear. But declarer had only shown up with two aces so far —surely, I thought, he had the ![]() A and we would spend the next ten minutes fiddling around to get Michael’s

A and we would spend the next ten minutes fiddling around to get Michael’s ![]() K. Why not cut short the torture, play a spade, and get the hell out of here? So I shifted to the

K. Why not cut short the torture, play a spade, and get the hell out of here? So I shifted to the ![]() 10, declarer played low, and now — in my haste to solve all the problems of the hand at once — I had given Michael a headache. Maybe he should have ducked the spade to dummy’s

10, declarer played low, and now — in my haste to solve all the problems of the hand at once — I had given Michael a headache. Maybe he should have ducked the spade to dummy’s ![]() Q — the slow defense that I had rejected — but maybe not, for he could not be sure of the club position. And he, too, wanted to get out of the room and compare scores. Perhaps even the cold-blooded Scots have emotions now and again. So he took the

Q — the slow defense that I had rejected — but maybe not, for he could not be sure of the club position. And he, too, wanted to get out of the room and compare scores. Perhaps even the cold-blooded Scots have emotions now and again. So he took the ![]() A — uh, oh… Declarer claimed his contract a moment later, and I felt sick. Imagining that this hand had cost us the tournament, I heard the last cheery bit of news from our opponents, who were one of the teams challenging us for the title. They started congratulating one another on the great session they had played. Just what I needed. A little sluggishly now, we walked outside, caught sight of our teammates, when — Aiiii! There it was — The Shriek, the dreaded Shriek. We had lost. Like a drowning man, my errors flashed before my eyes. But then I noticed a contradiction. Our teammates were walking towards us smiling, and one of them — Chris Compton —was offering me a double brandy. This had to be good news, because the last time Lev smiled was while he was watching Fiddler on the Roof for the twenty-third time, and nobody could remember the last time Compton had bought anyone a drink. We compared scores quickly, and we had indeed won the Reisinger. Then why had I heard the Shriek?

A — uh, oh… Declarer claimed his contract a moment later, and I felt sick. Imagining that this hand had cost us the tournament, I heard the last cheery bit of news from our opponents, who were one of the teams challenging us for the title. They started congratulating one another on the great session they had played. Just what I needed. A little sluggishly now, we walked outside, caught sight of our teammates, when — Aiiii! There it was — The Shriek, the dreaded Shriek. We had lost. Like a drowning man, my errors flashed before my eyes. But then I noticed a contradiction. Our teammates were walking towards us smiling, and one of them — Chris Compton —was offering me a double brandy. This had to be good news, because the last time Lev smiled was while he was watching Fiddler on the Roof for the twenty-third time, and nobody could remember the last time Compton had bought anyone a drink. We compared scores quickly, and we had indeed won the Reisinger. Then why had I heard the Shriek?

Lev is an Israeli, I am from Pakistan, and Molson is a Canadian. Though Compton is an American, he isn’t four Americans, so that meant our team would not be eligible to represent the US in international competition — we could not play in the Trials. Thus the second-placed team — a trio of mixed pairs and real-life sweethearts — had won their place in the US Trials and had truly earned the right to Shriek with delight. The moral? At bridge, no one can hear you scream…