Source: THINKING ON DEFENSE: The art of visualization at bridge By Jim Priebe

Visualization is a form of lateral thinking, the mental process of exploring multiple possibilities and approaches instead of pursuing a single approach. To a defender, exploring multiple possibilities means training yourself to construct and examine several potential declarer hands as you plan each defensive campaign. You sift through two, three or four alternative hands, and only then make your decision on what card to play. You are careful in the use of instinctive plays — these are the cliches of bridge, and are usually poison to defenders; for example:

• never lead trumps;

• always return partner’s lead;

• third hand high;

• second hand low;

• lead through strength, up to weakness.

These statements have value for whist and euchre players, and for beginning bridge players. They have no place in the arsenal of an aspiring defensive expert. You need a specific reason for every card that you play (which may just be hope in some cases!) based on your visualization of declarer’s hand.

ACQUIRING VISUALIZATION SKILLS

Visualizing unseen hands means thinking through alternatives. As a good defender, you mentally construct three or four possible hands, select one or two where a play is critical, and only then play your card. During a session of twenty-six boards you can expect to encounter two or three difficult defensive problems. Each of these hands will have a turning point where the play that you choose will be the sole factor determining the result. At that defensive turning point, the bidding is history, the opening lead has done its damage, declarer may have fired his best shot, and the defense is in charge. Getting those critical hands right each session will improve your matchpoint percentages markedly and make you a sought-after teammate for IMP matches. On defense, you compile information from the bidding, from partner’s lead and signals, and from declarer’s tactics. As you ponder what you should play, you will probably not know your side’s exact assets. In piecing together a hand for declarer (and thus for partner) you must engage in a certain amount of guesswork. While a good defender frequently guesses correctly, it is easy to fall into the trap of assigning one specific hand to declarer and basing your whole defense on that hand. Later, when the specific layout is clear, you may find that you have missed the mark.

When you pause to visualize, you need to form a mental picture of a range of possibilities instead of just one possible hand. You want the range to be small enough so that you can get your mind around it, but broad enough so that you do not overlook any hand that is reasonably possible for declarer. Even at an early stage of a hand there is useful information to help define the range. Notrump bids, five-card majors, and any number of special conventions are revealing. Leads, signals, and the first few tricks all add vital data. The goal of the visualization process is to make sure that you, the defender, like a good strategist in business, war or politics, consider the alternatives broadly enough to make a good decision.

With a few possible hands for declarer in mind, then, you set about the task of eliminating those where your task is hopeless. For example, if a hand does not jibe with information from partner’s lead and signals, move on. if your count of points and distribution tells you that a hand is impossible, ignore it. Playing IMPs, drop from further consideration any hand that means the contract cannot be set. When do you pause and carry out your visualization? Start before the first trick has been turned over. Routine hands look after themselves; only difficult hands require an investment of significant mental effort. On these difficult hands, the defender must start early and be ready for the turning point. If you are not ready when the time comes, your hesitation itself may cost the contract.

STEP BY STEP

You may be asking yourself, ‘Are there any shortcuts in the visualization process? Must I go through this lengthy analysis on every hand I play?’ This depends on where you are in your development as a defensive player. Many hands can be analyzed with reference to one suit only, or one or two key suits. You can see clearly that partner needs a specific holding to give you any chance of a good result: at IMPs, setting the contract, or at matchpoints, taking the maximum number of tricks. The more experienced you are, the easier and shorter the visualization process becomes. Let us follow these themes through the defense of a single hand; then, change the hand and see how the approach changes.

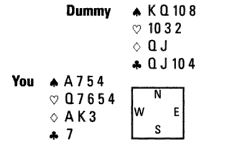

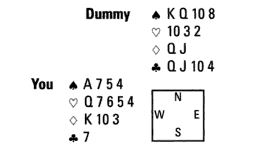

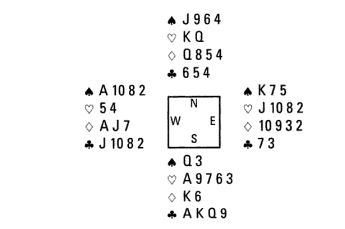

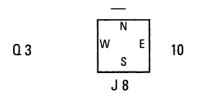

Your opponents settle in 3NT after South opens a 15-17 notrump and North’s Stayman enquiry reveals that he has no four-card major. Your heart lead is won by declarer’s jack. Quick, what are you going to do when declarer immediately plays a low spade? You, as West, must be ready when declarer’s spade hits the table. All of your thinking must be done before you turn over the first trick. Ducking even one spade is dangerous. Declarer is marked with all the outstanding high cards (the ace, king, jack of hearts and the ace, king of clubs). If declarer has five clubs, one spade trick will let him waltz away with his contract. You need to find partner with some diamond holding such as 109xx, 10xxxx, or xxxxxx; any of those holdings produces five, six or seven tricks for the defense. It takes little or no analysis to see that rising with the ace of spades and playing diamonds is the right defense. Remove the jack of spades from your hand and you have a slightly different problem after the same play to Trick 1:

Again, declarer surely has the ace and king of clubs, and the ace, king, and jack of hearts. The important unknown factors here are the number of clubs declarer holds and the locations of the ten of diamonds and the Jack of spades. We can construct possible hands around the table, and then analyze them to see where they lead the defense.

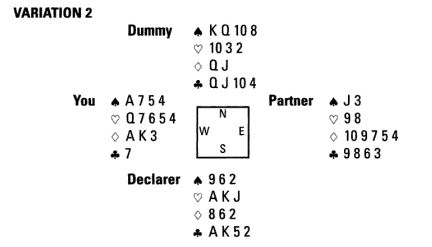

In this variation, if you win the first spade and play three rounds of diamonds, declarer has all his work done for him, and makes ten tricks. This is not a great issue at IMPs, but at matchpoints the play delivers a below-average result for the defense. Declarer can achieve this result himself by guessing the spade position, but ducking the spade gives the defense hope for four tricks.

Here, the defense gets two chances, because declarer needs two spade tricks for his contract. If you duck the second spade, declarer is home. He will surely play you for the ace of spades because he cannot afford to lose the lead. If you win either the first or second spade, the defense can take six tricks.

Now ducking one spade is a disaster because that is declarer’s ninth trick. You must win the ace of spades the first time spades are led, and play diamonds. We could go on, but three examples are plenty at this stage. In all three cases we constructed, it costs nothing to win the ace of spades at IMPs, while ducking can never gain. At matchpoints, the choice of play is perhaps not as clear. If we change your diamond holding to A32 or K32, the same idea is valid. You can tell that declarer either has solid clubs or is traveling to dummy to finesse against partner’s club king, a play that will bring good news. If declarer lacks the king of clubs, he surely has a diamond honor. Let us look at this new variation to see what we can learn.

Rising with the ace of spades and shifting to a diamond will lead to declarer making five notrump. He could do this himself, but needs to guess the spade position. If your diamonds were  A32, the same result would ensue.

A32, the same result would ensue.

From this point on, instead of showing variations with a diagram of all four bands, I will show only your band and dummy, to define the problem. Then I will suggest two or more possible bands for declarer. The constructed hands will take into account the information available to the defenders from the bidding and from partner’s and declarer’s play to date. This mimics the real process of visualization that I am recommending. The same approach is used throughout the other example and problem hands in the book.

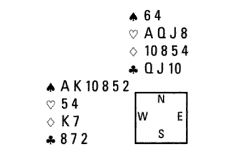

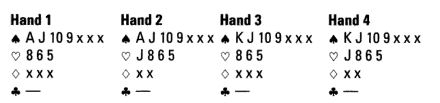

With a diamond holding of K103 or A103, the defense is less certain. Suppose this is the problem you see after your heart lead is again won by the jack, and declarer tables a low spade:

You can consider three possible hands for declarer as you plan your defense.

Against Hand 1, you have the luxury of two chances to set the hand: winning either the first or second spade and shifting to a diamond will give the defense six tricks. However, you must either shift to the king of diamonds and then play the ten, or shift to the ten, and with either of these leads you are bound to give partner a problem. Leading the ten suggests a poor diamond holding, perhaps with ace, queen to five hearts and the need for partner to lead a heart through declarer. Leading the diamond king and following with the ten will suggest a doubleton dia-mond. However, if you lead the diamond ten, partner should work out that you cannot hold AQxxx in hearts because there would have been absolutely no rush to win the ace of spades and shift to a diamond. The only reason to rise with the ace of spades would be in the case where the defense must work on diamonds quickly. Partner can also reasonably reject a layout where a heart return is vital, such as the following declarer hand:

xxx

xxx  KJx

KJx  Kxx

Kxx  AKxx

AKxx

While possible, this would be a sub-minimum hand for a 15-17 notrump bid. If you switch to the king of diamonds and continue with the ten, partner will not have a problem if he holds A98x, A9xxx, or A8xxxx in the suit. He cannot go wrong either by ducking or by overtaking the ten. If partner has A8xx or A8xxx maximum damage has already been done, and declarer will be thankful of your help (Hand 4).

Against Hand 2, winning the ace of spades and shifting to a diamond allows declarer to make eleven tricks. He could do this himself of course, but your ducking the spade twice would give him a chance to misguess spades and hold himself to one overtrick.

Against Hand 3, you must win the ace of spades at your first opportunity and play diamonds; otherwise declarer will make his impossible game. The contrast in thinking between IMPs and matchpoints stands out here. At IMPs, you have a very good chance of setting the contract if partner has a suitable diamond holding, and it is worth risking the loss of 1 IMP in pursuit of a 10- or 12-IMP gain (or avoidance of a similar loss if your counterpart at the other table finds the winning defense). At matchpoints, there is more to be said for ducking the spade twice because you preserve some chance for an above-average score. My recommendation for matchpoint players is that whenever you have a choice of two lines of defense which appear equally reasonable, you should adopt the route that leads to setting the contract. You get a bigger payoff (a near top for a set versus an above-average score for holding the contract tight).

THE PROCESS OF VISUALIZATION

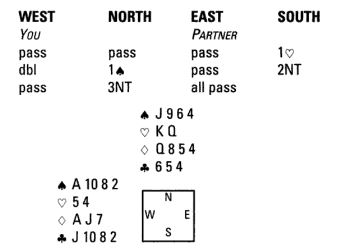

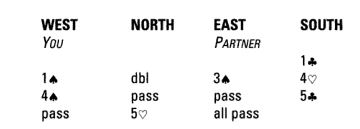

This real-life example illustrates how a defender can use information from only the bidding to arrive at a winning play. This is the auction:

You lead the king of spades and see this layout:

Partner plays the nine (a count card in this situation, showing an even number) and declarer the three. Your agreement with partner about the meaning of the three-spades bid is that it shows a constructive hand with four trumps but less than a limit raise. You review your chances and mentally synthesize a few possible hands for declarer. The outstanding high cards to account for here are the heart king, the ace and queen of diamonds, and the ace and king of clubs. Declarer no doubt has three or four of those cards. You know that declarer has four hearts and five or six clubs. These are the hands you imagine as you work out your play to Trick 2.

With Hand 1 declarer can take three heart tricks, five clubs, a diamond and a spade ruff in hand for ten tricks. The defense must be patient about their diamond trick because switching to a diamond now hands declarer his eleventh trick. Declarer’s hand here is one that few players would open, let alone take to the five-level. With Hand 2, declarer has four hearts, four clubs, a spade ruff and the ace of diamonds for ten tricks. A diamond switch again allows declarer to make an impossible game.

Defending against Hand 3, a diamond switch at Trick 2 allows the defense to cash the first three tricks, and against Hand 4, the diamond play lets partner cash a diamond when he wins the king of trumps. Now we have a dilemma. On Hands 1 and 2, we must wait for a diamond trick, and on Hands 3 and 4, we must play a diamond immediately or we give up an unmakable game. What is the answer? In this case, we should trust the opponents’ bidding. The auction is much more credible when declarer holds six clubs, and offensive potential, than if he has only a five-card suit and reasonable defensive prospects. Therefore, the recommended play is the king of diamonds at Trick 2. In fact, this was the actual deal (declarer had Hand 3 above):

CONSTRUCTING POSSIBILITIES

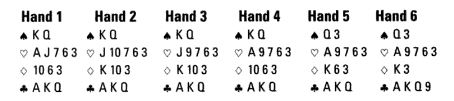

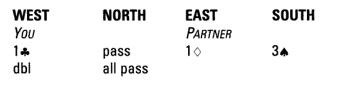

The next three problems expand on the mental process of visualization. In each case, I am going to show two or more possible hands for declarer that are consistent with the bidding, with partner’s lead and signals, and with the play so far. You will find that with some good hard mental effort, you become increasingly proficient at making the right decision. Modern bidders understand that the better they can describe their hand patterns and high card values, the better their chances of getting to the right contract. They are right, but in the process, they provide help to the defenders. Such conventions as Flannery 20, mini-Roman 20 and two-suited two-bids provide precise information about distribution and high cards to the defense as well as to the offense. Five-card majors and narrow-ranged bids such as notrump calls provide inferences about strength and distribution that are useful to a defender trying to visualize possible declarer hands. Here is such a case. You lead the jack of clubs against 3NT after the bidding has gone:

Partner follows with the three and declarer wins the queen. Declarer crosses to the king of hearts as partner follows low, and leads the four of spades to partner’s three and his queen. You win the ace and pause to consider your defense. In order to illustrate the method, I will show six possible hands in this problem, more than a defender usually looks at. The auction suggests that declarer is 5332, but you cannot yet rule out 5422 hands. Partner’s attitude signal at Trick 1 tells you that declarer has nine points in clubs – half of his assets. When declarer shows the queen of spades, you can account for eleven of his eighteen or nineteen points. This leaves him with seven or eight other points. The three main outstanding high cards are the king of spades, the king of diamonds, and the ace of hearts. Partner has one of those cards, but at this point you do not know which one. These hands ought to bracket the possibilities.

Hands 1 and 2, where declarer’s heart holding fits so well with dummy, always produce nine tricks. If you are going to set declarer, you need to find partner with some useful holding in hearts. That reasoning leads you to Hands 3 through 6, all of which can be set. But how should you tackle them? With Hands 3 and 4, declarer’s best play was to start spades while he had a sure entry to dummy, hoping to see the ten of spades fall. A little luck in spades or a good heart split would give him his nine tricks. Against a strong declarer, you can discount these two hands, and focus on 5 and 6. A club return is fine with Hand 5, but is disastrous with Hand 6. A diamond return loses in both cases. A spade or a heart return looks safe on both hands, and a heart is preferable because it interferes with declarer’s communications. If declarer plays a diamond to his king, partner’s count signal will tell you how to continue. If he shows three diamonds, you can exit with a club (Hand 5), and if he shows four diamonds (Hand 6) you can return the jack of diamonds. Finally; if declarer returns to hand with a club, partner’s card will tell you if declarer started with three or four cards in that suit and you will know whether you are facing Hand 5 or Hand 6. This deal has many variations. It shows how a defender can build up possible hands for declarer and then avoid committing to an early losing play by waiting until there is enough information to deduce the winning line. This was the actual deal:

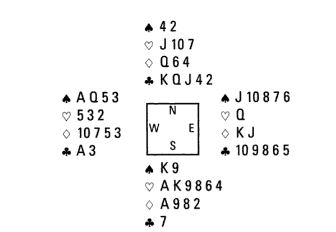

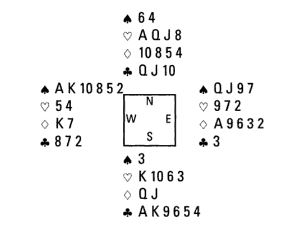

Now let’s try another one, this time a deal with some significance in bridge history. This is the bidding (both vulnerable):

You lead the king of clubs against three spades doubled, and here is what you see as declarer ruffs your club:

Declarer now leads a low heart from hand and at Trick 2 you have already reached the turning point of the hand. Your double promises plenty of high cards but not a spade stack, so partner needs some defensive values to leave it in. Declarer is vulnerable, so he rates to have a decent seven-card suit. In any case, you can see that with eight trumps he will always take ten tricks. You are therefore going to play declarer for six red-suit cards, distributed either 3-3 or 4-2. If his spades are solid, declarer again has ten tricks, so you must assume partner has the ace or king of spades. Partner should also have the king of diamonds. What does that leave for possible declarer hands?

The defense needed a trump lead to set Hands 1 and 2, and both are cold now, so you might as well focus your energy on Hands 3 and 4. Declarer has eight tricks in both cases, and if he can trump a red-suit card in dummy, he has nine. The defense must lead ace and another trump on gaining the lead. Why not win the ace of hearts right now and lead a spade, then? That works fine against Hand 3, but against Hand 4, on that defense, declarer has good enough heart spots to force a ninth trick. You must duck the heart, and if partner can win the second heart, you must trust that he realizes the necessity of playing ace and another spade.

The whole deal was:

This deal determined the outcome of the 1982 World Championship, where the Trick 2 play by West was indeed the turning point. West rose with the ace of hearts to play trumps and the French declarer found the right continuation in hearts (Hand 4). The heart posicion around the table after West rose with the ace and declarer subsequently played the king was:

When the declarer guessed to lead the jack from hand, smothering the ten, he made his contract, and the American team lost 14 IMPs on the board. Trick 2 on this deal was truly the turning point of the whole World Championship final match because this misdefense led to the US team falling behind. This in turn necessitated an anti-percentage play by an American declarer in a later 3NT contract to try to create a swing. (The anti-percentage play was correct at that stage of the match but resulted in the loss of ten more IMPs). France won the final by 17 1MPs. Of count, a 3NT bid by East on our example deal would have won the championship outright for the Americans.

When the declarer guessed to lead the jack from hand, smothering the ten, he made his contract, and the American team lost 14 IMPs on the board. Trick 2 on this deal was truly the turning point of the whole World Championship final match because this misdefense led to the US team falling behind. This in turn necessitated an anti-percentage play by an American declarer in a later 3NT contract to try to create a swing. (The anti-percentage play was correct at that stage of the match but resulted in the loss of ten more IMPs). France won the final by 17 1MPs. Of count, a 3NT bid by East on our example deal would have won the championship outright for the Americans.

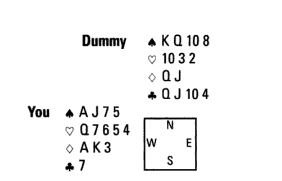

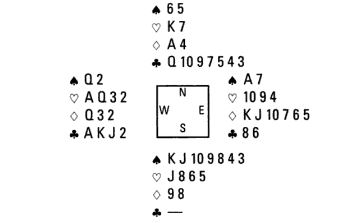

Our third problem also offers a reward for a thoughtful defender.

You lead your three of diamonds, declarer plays dummy’s queen, and partner the king. Declarer wins the diamond ace, cashes the ace of hearts, felling partner’s queen, then plays the seven of clubs. What are some possible hands for declarer? He has six hearts, based on partner’s queen play. He may or may not have the spade king.

At IMPs, you need four tricks. In addition to your aces, partner needs a diamond trick which will serve as an entry to lead a spade through. Against Hand 1, you can relax — declarer has only eight tricks. Just remember to lead a diamond when you win the ace of clubs. Hand 2 requires that you sit up. If you duck a club, declarer can ruff out your ace, cross to dummy while drawing trumps, pitch his spades, and give up two diamonds to make his contract. You must rise with the ace of clubs now and return a diamond. Partner will win the jack and shift to a spade. You can cash two spades and another diamond for down two. Hand 3 always makes. If you cash spades, declarer uses the dubs to pitch losing diamonds. If you lead a diamond back, declarer will win, draw trumps, and pitch two losing spades and a diamond. You get the last diamond. Therefore, the defense that covers those hands that can be set is to rise with the ace of clubs, return a diamond, and hope!

At matchpoints, you would have to consider cashing out your spade trick(s) and holding declarer to either four or five (depending on who has the king of spades).This line of defense gains a trick against Hand 3 but costs the contract against Hand 2, and an extra downtrick against Hand 1.

PLAYING IN TEMPO

The expert makes a practice of planning his defense at a time when no particular inference can be drawn from his pause. Marshall Miles, All Fifty-two Cards.

One concern of anyone deciding to work on visualization skills will be, Am I going to slow down play on every contract I defend?’ My answer is, certainly you are. But what if you do? Bridge is a game for thinkers, and no one will achieve consistently good results without investing in thinking time at the table. If you are a slow player, frequently in time trouble, look elsewhere for ways to improve your speed – cut down on discussions at the table or make your comfort breaks more efficient. Don’t cut into your thinking time. You have to develop good thinking habits. In defense, that means visualizing the unseen hands, and especially, letting your mind roam over a few alternatives before making a play in a pivotal situation. Unless one is blessed with the lightning speed of an Oswald Jacoby or a Jeff Meckstroth, one needs practice to improve the ability to visualize; that is, players must train themselves to visualize unseen hands in developing defensive plans. With practice and some hard work away from the table, a player can improve his speed of play. Bridge is not a speed contest. No one can play good defense by rushing. The rewarding aspect of all this is that, the harder you work at it, the faster you become at analysis, and (the real payoff) the more accurate you become. Much defensive card play is second nature to a regular player. It seems routine. But if you kibitz an expert table in a National event, especially the late stages of the Vanderbilt or the Spingold, you will see that the players take plenty of time to work through alternatives. If you have ambitions to become a strong defender, you will invest the time to visualize alternatives in working out the optimum defense on every hand you play. No one can be perfect, but raising one’s average percentage by even a few points means the difference between a journeyman cam-paigner and a dangerous contender.

SUMMARY OF THE VISUALIZATION PROCESS

The goal of the visualization process is to make sure that, as a defender, you consider alternatives broadly enough to make good decisions. As a defender:

Start the process at Trick 1. Remember that a hesitation at the key moment may itself cost the contract.

Form a mental picture of several possible hands for declarer instead of just one hand. Make your picture small enough to get our mind around it, but broad enough that you do not overlook any reasonable possibility for declarer (usually three or four hands).

Mull over information from the bidding, from partner’s lead and signals, and from declarer’s tactics. Remember that even at an early stage of a hand there is useful information to help you define your mental picture. Notrump bids, five-card majors, and any number of special conventions are revealing. Leads, signals, and the early play all add vital data.

With three or four hands in mind, eliminate those that do not belong. If a hand does not jibe with partner’s lead and signals, move on. If your count of points and distribution tells you the hand is impossible, throw it out.

Make the winning play!

Esta entrada también está disponible en: Spanish