Source: Master Play in Contract Bridge By Terence Reese

How Could I tell? I / How Could I tell? II / How Could I tell? III

“There was no way in which I could tell.” How often is it true?

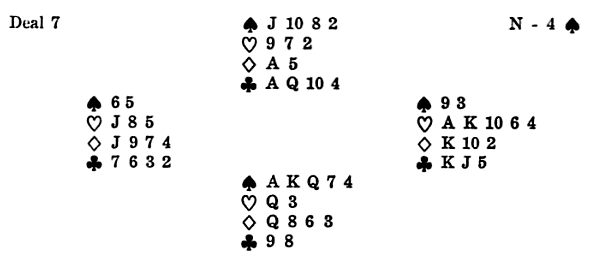

To Bed with an Ace

When the defenders have two top tricks to make against a slam contract, they often have a problem in finding them soon enough. Every player has had the experience of sitting with an ace after his partner has won an early trick, waiting in agony for partner to make the right lead. This is especially true when the defenders have two aces—something they do not expect. Even though this particular trap is avoided (in favour of many others) by addicts of the Blackwood convention, it is sometimes difficult to stay out of a slam when all the high cards are held except for two aces.

On this occasion Sur opened 1 , Norte bid 2

, Norte bid 2 and Sur 2NT. With 16 points and a five-card suit Norte made a slam try of 4 NT. As Sur had a fair hand for his bidding up to date he took a chance on 6NT, and there they were with abundant tricks but two aces missing.

and Sur 2NT. With 16 points and a five-card suit Norte made a slam try of 4 NT. As Sur had a fair hand for his bidding up to date he took a chance on 6NT, and there they were with abundant tricks but two aces missing.

Oeste opened  7. Sur won with jack and led a low diamante on which Oeste naturally played low. Dummy’s jack held the trick and a low spade was returned to the queen. Declarer then led

7. Sur won with jack and led a low diamante on which Oeste naturally played low. Dummy’s jack held the trick and a low spade was returned to the queen. Declarer then led  J and Este won with ace. Now Este led a corazon and Sur was able to run off twelve tricks by way of three spades, five corazons, one diamante and three clubs.

J and Este won with ace. Now Este led a corazon and Sur was able to run off twelve tricks by way of three spades, five corazons, one diamante and three clubs.

Este explained that he placed Sur with  A-x-x and thought the only chance was to win a corazon trick quickly. Can you say where that argument breaks down?

A-x-x and thought the only chance was to win a corazon trick quickly. Can you say where that argument breaks down?

Suppose that Este had been right in his analysis of the diamante situation. That would give the declarer five tricks in diamantes, three in spades and (in all probability) three in clubs. He still could not make the slam without the  A. So, there could be no advantage in leading a corazon now: if Este had arrived at that conclusion, he might have thought again about the

A. So, there could be no advantage in leading a corazon now: if Este had arrived at that conclusion, he might have thought again about the  A.

A.

Counting the Tricks

On the last hand the defender’s play was based not so much on inference as on counting declarer’s possible tricks. These are some more hands on which the obvious play will fail and the defender will do the right thing only if he keeps an intelligent count and looks deeply into the position.

Sur played in 4  after Este had opened 1

after Este had opened 1 . The corazons were led and continued, and Sur ruffed the third round. After drawing trumps Sur led

. The corazons were led and continued, and Sur ruffed the third round. After drawing trumps Sur led  8, running it to Este’s jack.

8, running it to Este’s jack.

An average player in Este’s position, noting that a corazon or club return would certainly give up a trick, would try a diamante. As Este, in actual play, was not hopeful of finding his partner with the  Q, he studied the other possibilities. In most elimination positions, when a defender has to choose between conceding a ruff and discard and leading into a tenace, it is better to allow the ruff and discard. Thinking along these lines, Este constructed for Sur a 5-2-3-3 hand, including

Q, he studied the other possibilities. In most elimination positions, when a defender has to choose between conceding a ruff and discard and leading into a tenace, it is better to allow the ruff and discard. Thinking along these lines, Este constructed for Sur a 5-2-3-3 hand, including  Q.

Q.

If that were Sur’s hand, a corazon would not help him: if he discarded a club from his own hand he would have to lose a diamante, and if he discarded a diamante from dummy he would have to lose a club. Having reached this point in his analysis, Este led a corazon, but that was not good enough against the actual distribution.

Sur ruffed in his own hand, discarding a diamante from table. Then he led a club to the ace and established another club trick by leading through Este’s king. Two diamantes were ruffed and one went away on the established  10.

10.

The play that looked the least attractive of the three would have worked against any distribution. Sur was known to have six cards in the minor suits. If a club return gave him two discards, he would still have to lose a diamante. The short way to this conclusion was to reflect that Sur had on top five tricks in spades, one in diamantes and, at most, three in clubs; that is only nine, so he would have to lose a diamante after a club return.

Esta entrada también está disponible en: Spanish