Extracted from the article How Good Are You? by Charles Goren for [ilink url=”http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/”]Sports Illustrated[/ilink]

In taking up this very pleasant assignment, I have realized a lifelong ambition. At a time when most lads yearn to grow up to be cops, I was seized with a burning desire to become a sportswriter, an urge which grew almost irresistible when it became apparent that I lacked the talent to become a successful competitor.

Up to now, the closest I ever came was when I was a student at McGill University (where, some while later, four young ladies were to lure me into my very first game of bridge). I had been assigned to cover one of the important hockey matches of the season. My selection for this task was of doubtful wisdom, for I had never before seen so much as a single chukker of ice polo.

I have a vague recollection of treating the spectacle as though it were the Easter Parade, but I was disappointed when a painstaking perusal of the next editions failed to reveal a trace of my masterpiece in the sports columns or anywhere else. When I summoned up courage to inquire if my story was bad, the editor was consoling. “Not bad at all, Goren. In fact, it was reasonably good,” he soothed, “even though it had no relationship to hockey.”

In recent years I have tried to scramble onto the sports page by pointing out to hardheaded sports editors that bridge has its heroes and its goats, its rabid rooters and its second-guessing quarterbacks, plus a fierce competitive element equal to that found in more active sports. They continued to report doings at the billiard table, the ping-pong table, even the chess table—but the bridge table? No, that would be carrying things too far.

At last, using the gifted pen of Somerset Maugham as a springboard, I am about to hurdle the long-standing barrier that has kept contract bridge off the sports page where it really belongs. I confess to a bit of stage fright, but I intend to write about bridge as a sport and expect to report anything which I believe the reader will find diverting.

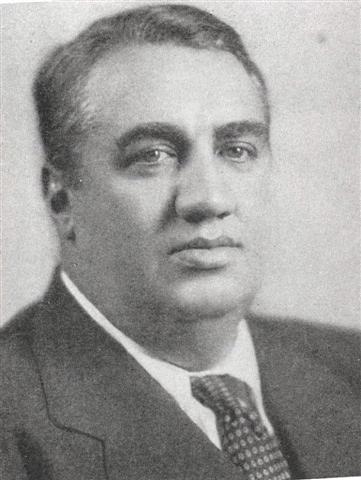

Occasionally we shall dig into our personal archives for an unpublished hand of the nature of the one shown today. It was a perpetration of Hal Sims, who, despite his 300 pounds, could afford to play high-stake golf in a foursome with three professionals provided they would in turn play a few rubbers of high-stake bridge. The story has been filed under the caption “The Hand Is Quicker Than The Eye.” The tournament involving this hand—a National Championship at Asbury Park, New Jersey—produced an offstage sensation in the shape of a bout of fisticuffs between Sims and another of the game’s top-weights.

To a bridge player there is one thing more frustrating than bidding a grand slam in no trump lacking an ace. That is to hold an ace against a no-trump grand slam and never win a trick with it. In this remarkable deal East was victimized by Sims’s neat bit of hocus-pocus. But he first fell victim to his own greed.

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

With both sides vulnerable, South (Sims) dealt. The bidding went:

| West | North | East | South |

| 1 |

|||

| Pass | 3 |

Pass | 3 |

| Pass | 6 |

Double | 6NT |

| Pass | 7NT | Double | Pass |

| Pass | Pass |

Perhaps South’s cue bid in spades was unwise, especially in view of his partner’s weird leap to six in that suit, and his unrealistic push to a grand slam after Sims bid six no trump, trying to extricate himself from six spades.

East was guilty of avarice when he doubled six spades. He was to pay dearly for it. From the sound and fury of East’s doubles, West’s lead of a spade was entirely logical.

Sims counted 12 tricks: five hearts, five clubs and two spades. A successful spade finesse would produce the 13th—but it was impossible that the spade finesse could succeed. Sims had to find another way of pulling a rabbit out of the hat.

He took dummy’s ace of spades and king of spades, discarding diamonds from his hand. Then, playing swiftly as he always did, Sims cashed his five club tricks, discarding a low spade and the lone diamond from North’s hand. Now he was ready for the hocus-pocus. He cashed his heart ace, “accidentally—on purpose” playing dummy’s 4. He played his heart jack, overtaking with dummy’s queen. And he continued leading down the hearts until dummy remained on lead with the lowly 3.

East knew, of course, that South had another heart. He knew, too, that South did not have a spade. So he threw away the queen of spades in order to hold his ace of diamonds, expecting that South would win the last heart trick.

But East had taken his eye off the ball. When South produced his last heart, instead of being one that would win the trick and force him to surrender a diamond to East’s ace, it was the lowly deuce—small enough to crawl under dummy’s 3. So North, not South, won the 12th trick. And North, not East, won the vital 13th that brought home the grand slam.

It would be an appalling task to remember all 52 cards in every deal, and it is seldom necessary to do so. Let’s see, for example, how East might have concentrated his attention upon the trey and deuce of hearts.

After the very first trick East could forget about the spades except for those he could see in North’s hand, because South had already shown out. The next three tricks eliminated his concern about clubs. And from South’s discards on tricks one and two, it was obvious that the only diamond of any consequence to East was his own ace.

Skillful deception

That left his mind free to concentrate upon hearts. The reason he was led astray, however, was that it did not seem important to him—since he did not have a heart in his hand—to pay much attention to that suit. Against the skillful deceptive tactics of an operator like Sims, even a foremost expert might have been taken off guard. It’s all very human, which makes contract bridge such great fun.

Let me offer a few suggestions that may serve to jog your memory.

First: Take a good look at the cards that have been played, for it will be impossible to recall what you have not seen. A careful concentration on each trick before it is turned may serve to imprint a photograph in your mind, one that you can pull out of the files later, if it should become necessary. However, in many cases you will find that it won’t be necessary.

Second: It is the height of futility to try to remember all the cards that have been played. Start by remembering only what card is now high. Suppose, for example, the first two leads of a suit have slaughtered the six highest cards. Instead of remembering that the ace, king, queen, jack, 10 and 9 have been played, you can catalog the same information by remembering that the 8 is high.

Third: Make a special effort to remember the discards. Most tricks in bridge consist of four cards in the same suit. If you remember those tricks in which some player fails to follow suit and recall how many times the suit was led, it will be a relatively simple task to calculate how many of that suit have already been played.

Can you then be confident that you will know the 3 to be high? Probably not. But you will rarely run up against the kind of legerdemain to which East was subjected in that deal.

Esta entrada también está disponible en: Spanish