Fuente: www.vba.asn.au

Consider this auction over the course of history:

![]()

Let’s put some hands and decades to it:

1960s. Responder holds: ![]()

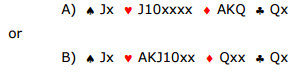

Opener responds 5 to simple Blackwood, one ace. But does he have:

to simple Blackwood, one ace. But does he have:

Slam might have no play or be cold, and the one-ace reply doesn’t tell you which.

You really need to know about that king of hearts. The king of the agreed trump suit is almost as good as an ace. It’s true that a missing trump king might not translate to a loser – you could win a finesse; however, it’s not a bad strategy to stay out of a slam that needs a finesse. And of course, no finesse will help when the missing trump king is accompanied by the missing trump ace!

So along came Key-Card Blackwood, where the king of the agreed trump suit1 counted as an ace … there were now 5 “aces” instead of 4. Hand A) bids 5 (one or four key cards), and Blackwooder signs off in 5

(one or four key cards), and Blackwooder signs off in 5 , as he is missing two key cards. Hand B) bids 5

, as he is missing two key cards. Hand B) bids 5 (two key cards), and Blackwooder goes to slam.

(two key cards), and Blackwooder goes to slam.

Simple and effective.

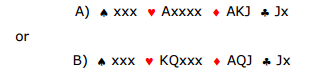

Until: 1980s. Responder holds: ![]()

Opener responds 5 to key-card Blackwood, two key cards. But does he have:

to key-card Blackwood, two key cards. But does he have:

Slam might have nearly no play or be almost cold, and the two-key reply doesn’t tell you which. So along came Roman Key-Card Blackwood, where the queen of trumps also plays a part. The responses are:

- 5

: zero or three key-cards

: zero or three key-cards - 5

: one or four key-cards

: one or four key-cards - 5

: two key-cards, no trump queen

: two key-cards, no trump queen - 5

: two key-cards with trump queen

: two key-cards with trump queen

After a 5 or 5

or 5 response, Blackwooder can bid the next step (if below 5 of the agreed trump suit) to ask responder whether he has the trump queen.

response, Blackwooder can bid the next step (if below 5 of the agreed trump suit) to ask responder whether he has the trump queen.

Hand A) bids 5 (two key-cards, no trump queen), and Blackwooder passes, missing a key-card and the trump queen. Hand B) bids 5

(two key-cards, no trump queen), and Blackwooder passes, missing a key-card and the trump queen. Hand B) bids 5 (two key-cards and the trump queen), and the slam is bid.

(two key-cards and the trump queen), and the slam is bid.

By the way, if the responder to Blackwood estimates that the trump fit is at least 10 cards long, then he should “show” the trump queen, even though he doesn’t have it.

For example: ![]()

would be a 5 response – two key cards plus the heart queen. Partner is likely to have three trumps in this auction, so there is probably no heart loser, even missing

response – two key cards plus the heart queen. Partner is likely to have three trumps in this auction, so there is probably no heart loser, even missing  Q.

Q.

The method isn’t full-proof. For example, add the 10 and 9 of hearts to hand A), and slam becomes good again. But it works most of the time, and is certainly superior to not having any way to find out about the trump queen.

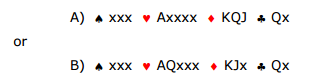

Until: 2000s. Responder holds: ![]()

Opener responds 5 to key-card Blackwood, one key card. But does he have:

to key-card Blackwood, one key card. But does he have:

Slam might have nearly no play or be almost cold, depending on that heart queen.

The problem this time is that there is no room for Blackwooder to make the secondary ask about the trump queen: there is no space between 5 and 5

and 5 .

.

So along came the 1430 convention, which modifies the 5 and 5

and 5 responses as follows:

responses as follows:

- 5

: one or four key-cards (“14”)

: one or four key-cards (“14”) - 5

: zero or three key-cards (“30”)

: zero or three key-cards (“30”)

The theory behind 1430 is that a one key response is more likely to require the followup of a secondary queen ask than a zero key card response.

This can have a payoff in particular if hearts is the agreed trump suit. In the example above, the response to “1430” is 5 (one or four key-cards), and now Blackwooder can bid 5

(one or four key-cards), and now Blackwooder can bid 5 asking: do you have the trump queen? Hand A) says “no” with a 5

asking: do you have the trump queen? Hand A) says “no” with a 5 bid, passed by Blackwooder. Hand B) says “yes” with a bid higher than 5

bid, passed by Blackwooder. Hand B) says “yes” with a bid higher than 5 .

.

1430 is a catchy name and has immense popularity, but I wonder whether it’s all worth it. Playing it when clubs is the agreed trump suit seems pointless: who wants to hear a 5 response showing no aces in a position where this means you are missing two aces? Maybe I am just stuck in the nineties!

response showing no aces in a position where this means you are missing two aces? Maybe I am just stuck in the nineties!

What will we all be doing in the 2020s? I don’t know, but the story of Blackwood – which we haven’t finished yet in this series, not by a long way – is a fine demonstration of the evolution of bidding theory.

… to be continued