Source: SI Vault May 07, 1962

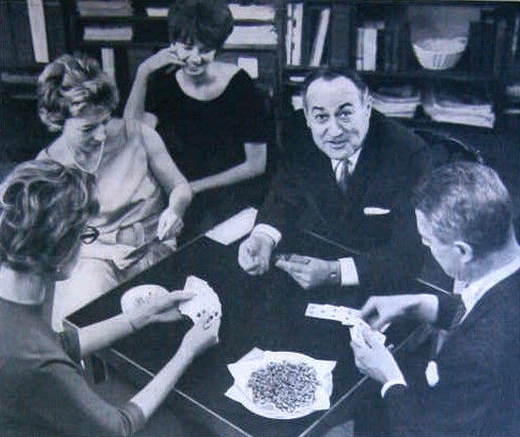

My good friend Dick Frey is well known these days as a bridge writer and commentator; he edits The Bulletin of the American Contract Bridge League and comments on the play at numerous Bridge-O-Rama shows where the public can view international and national team championships. But many newcomers to bridge are not aware that as long as 30 years ago he was one of the country’s top-ranking experts at the game he still plays so well.

When such a fine player operates as declarer in a hand he sometimes seems to perform as if he could see all the cards. A good example is this deal, which Frey played in the days when he was a member of the Four Aces, the team that dominated the biggest contract bridge tournaments during the early 1930s, twice winning each of the four major team events—the Vanderbilt, the Spingold, the Grand National and the Eastern Championships.

As you can see, good bidding has not altered a great deal in the past 30 years. West’s no-trump overcall is based on 17 points by present evaluation methods. South’s reverse bid—first diamonds, then spades—promised somewhat better than a minimum opening. North’s distributional values in support of spades added 8 points (5 for the void, 3 for the singleton) to the worth of his hand and merited his slam try. Frey, with the South hand, was happy to accept the invitation. And West could hardly believe what he heard! Only North’s redouble is subject to any severe criticism—but Frey’s play made that look good, too.

West did not have a comfortable opening lead. The king of clubs would have defeated the contract, but the actual choice of the club jack is more normal. North’s queen won the first trick. You are now at liberty to try making this contract while looking at all the cards because, with the bidding by West to guide him, Frey knew almost certainly where they all were located.

Dummy took the second trick with the ace of hearts, and declarer won the next five tricks by trumping hearts in his hand and diamonds in dummy. Danger developed, however, when East pitched three diamonds on the hearts. After ruffing the third heart, the situation was this:

Declarer cashed the ace of spades and led a diamond, driving out West’s ace. North carefully trumped with the 10, preventing East from overtrumping. Now all that remained was to play for one good break—finding the two outstanding trumps in different hands. They were. Dummy’s spade lead was won by West with the king, and East’s 9 dropped. West had nothing left to lead except a club, putting declarer in his hand with the ace. This meant that South, having discarded his 4 of clubs on the last trump lead, was left with two good diamonds which he could use to bring home his little slam.

EXTRA TRICK

The slam couldn’t be made if West held three trumps. South’s play was based on a sound principle: when you need a certain division of the cards in order to make your contract, you must assume that you’ll get it.

Esta entrada también está disponible en: Spanish