The Milwaukee Sentinel – 21 Sep 1934

THERE are many number of ways in which the declarer, being faced with a hopelessly lost contract, may cause his opponents to present him with an extra trick or two which he could not develop by straightforward play. In order to, pull the wool over the eyes of his adversaries he usually adopts an unsound line of play. The defending team, thinking of course that he is playing his cards according to conventional methods, receive an altogether erroneous impression of what cards he must hold in his hand, and this may tempt, them to make an incorrect lead or play. For many years bridge players, when playing a notrump contract, have attempted to conceal their weakness in a suit in which they hold no stopper by immediately playing that suit. If, for example, declarer holds J x x and dummy 10 x x, declarer leads that suit to convince his opponents he is trying to establish it. The opponents may as a result be afraid to play the suit themselves, for fear they will further declarer’s cause. Declarer may also lead a suit in which he has a single stopper giving up that stopper and leaving himself totally unprotected. Unfortunately, this method (which is merely a refinement of the course of deceptive play described in the preceding paragraph) is so obvious that it is too deep even for some of the most clever players to think of.

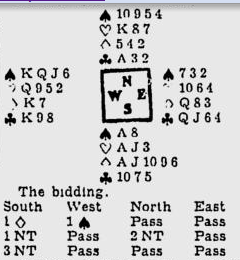

South: dealer, Neither side vulnerable.

South’s bidding was somewhat optimistic; the contract for nine tricks, after his partner had been unable to raise him on the first round, was very dangerous. Fortunately for bridge literature, however, it gave him an opportunity to make a superb psychological play.

West opened the spade king and South took the ace right away, to hold up would cost him a trick, if West continued with a low spade it was now obvious that there was hardly any chance for the contract since two finesses must be taken in diamonds and one in hearts. This would require three entries to dummy, whereas only two were available.

West surely had two spade tricks, and one club lead would establish at least three club tricks for the adversaries, in addition to the diamond which South must be prepared to give them. There was a glimmer of hope, however, if the adversaries could be persuaded either to lead a heart, or to establish a spade trick in dummy after winning their first diamond trick, then the contract would he made.

A lead to the king of hearts would assuredly discourage them from leading that suit, however; so South immediately and with a great air of assurance played the club 5, took dummy’s club ace and led a diamond. East played low and the jack was finessed to West’s king.

West could not lead spades, since that would set up dummy’s ten and he was afraid to lead clubs because it did not occur to him that South might so boldly have given up his only stopper. So West shifted to hearts right into South’s A J, and the nine tricks were automatically developed.

South won with the Jack of hearts, went over to dummy’s king and took another diamond finesse, and then ran down his diamond suit and his ace of hearts. A club lead by West would have defeated the contract two tricks. East might have dropped a hint to his partner by playing the club when North took the ace, but he did not want to reveal to South (whom he of course thought to have the king and ten) that he had the Q J. Anyway, the club 6 might not have meant a great deal to West, since the five, three and deuce were showing and it was quite possible that South had the four, in which case East’s six would be his lowest and convey no signal.